It’s October, and that means it’s time to celebrate one of America’s favorite holidays—Halloween! With the arrival of cooler fall weather and earlier evenings, we can indulge our sweet tooths with the spoils of trick-or-treating, decorate our homes and offices in cemetery chic, and binge watch hours of monster movies and creature features on Netflix. Break out the popcorn!

Two of the most well-known fictional features of the Halloween season must be Dr Frankenstein and his monster. Although the duo was first imagined by Mary Shelley in her 1818 novel, most of us probably picture the Colin Clive and Boris Karloff images from the 1931 film, Frankenstein. The mad scientist and his reanimated corpse have been the stuff of our collective nightmares for centuries now, but why is that? What about the Frankenstein story keeps us both frightened and fascinated after all these years?

Part of it has to do with the very things that make us human. Alongside walking upright and our opposable thumbs, our awareness of death and the way we react to it is considered one of the fundamental characteristics that set us apart from all other animals. We know we are going to die one day, and we place importance on the way we treat each other after death. Humans have developed a variety of funerary customs that differ among cultural groups, but all of them ritualize in some way what we believe should become of the body after death. None of those rituals have developed around the idea of donating bodies for study and research. But medicine as we know it would not exist without the ability to study and dissect human bodies after death.

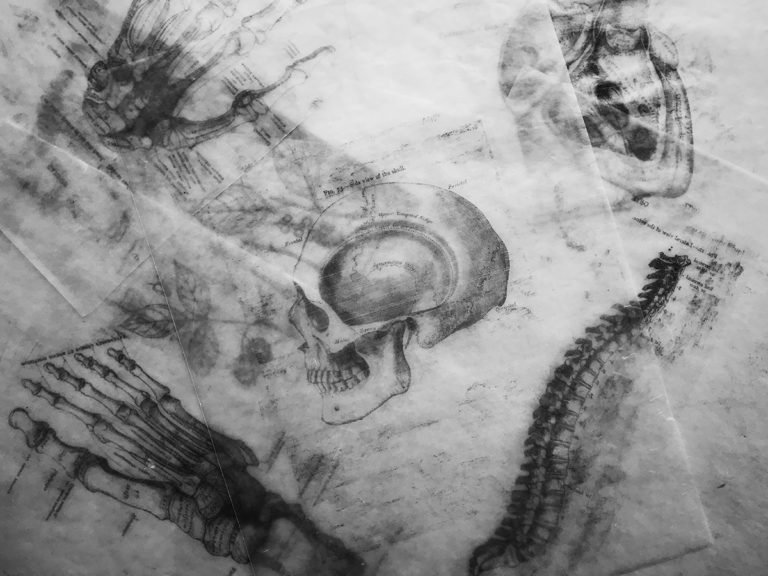

Before the third and fourth centuries BCE, our knowledge of medicine was based largely on observation, supposition, the study of animals, and the examination of human bones. Hippocrates (considered the father of medicine and the Hippocratic Oath) and Aristotle (the famous philosopher who developed the concept of evidence-based medicine) based their understanding of human anatomy on what could be deduced from studying the bones he found in the tombs, or from dissecting animals and trying to transfer that information to human bodies. Clearly, these methods had significant limitations.

It wasn’t until two Greek physicians in Alexandria, Egypt, Herophilus and Erasistratus, began to dissect the bodies of condemned criminals that medicine began to gather firsthand evidence of how the human body was constructed. Unfortunately, the Dark Ages and the rise of the Roman Catholic Church cast dissection for anatomical study in a negative light. Western culture turned its focus away from science and exploration and onto faith and religion. Until the 1300s, what we knew about the human body and therefore how to cure its injuries and diseases was relatively stagnant.

The rise of universities in medieval Europe reintroduced the study of cadavers to medicine and medical education. Requirements were laid down that anyone studying to become a doctor had to at least attend one anatomical dissection before they would be allowed to practice. This led to the inclusion of anatomy labs as part of a standard medical education. It also led to some rather unfortunate incidents in the history of medicine—most notably the macabre practices of body snatching and grave robbing which became commonplace in the 18th and 19th centuries.

The problem faced by the medical education system was that those religious and cultural norms for the treatment of the dead that developed during the middle ages made people view the idea of cadaver research as distasteful. Only criminals or the destitute were turned over to medical schools for dissection, so a stigma against the practice rose. This resulted in a shortage of bodies, a problem that persists even today.

Modern research relies on human cadavers for a lot more than the anatomy classes all doctors are required to take during their med school careers. Cadavers don’t just teach us about how the human body works. They provide information about how diseases can change the body and about how differences in anatomical structures can impact function. They allow doctors and surgeons to develop or learn new techniques without risking injury to patients. They allow researchers to develop new medical devices, like artificial joints or implantable drug delivery systems, and to test how they work before using them on the living. They help physicians and researchers understand how diseases like cancer or Alzheimer’s progress inside the body so that they can find better ways to treat or cure those conditions. They help develop protective gear to save the lives of our soldiers, or the child passengers in our cars and trucks. They can even help investigators learn to more efficiently solves crimes or to determine the causes of fires and other accidental deaths so that they can prevent them from happening in the future.

None of these things would be possible without body donation. While the details of operating rooms and dissection labs might make us think first about mad scientists like Dr Frankenstein, the reality is that doctors like Christiaan Barnard (the first surgeon to successfully transplant a human heart) could not have developed and perfected that operation without practice on human cadavers.

MedCure takes it responsibilities seriously, both our responsibility to our donors and our responsibility to the medical research and education communities we serve. Treating our generous donors with the utmost respect while also providing the unique support services we offer to researchers and physicians make for the kind of challenging and rewarding work we find most enriching. With the help of our donors, MedCure is helping to move science forward and save lives in the future.

How’s that for learning from history?